[ad_1]

This article is an onsite version of our Europe Express newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday and Saturday morning

Welcome back. Any publicity is good publicity, goes the saying. But I wonder if this holds true for Russia’s paramilitary Wagner group, whose role in the Ukraine war, not to mention domestic Russian politics, is steeped in controversy? You can find me at tony.barber@ft.com.

Two incidents this week shone light on the Wagner group, an organisation once so secretive that it had no formal legal existence, despite undertaking operations on the Kremlin’s behalf in places as far-flung as Ukraine, Syria, Libya and sub-Saharan Africa. Neither incident enhanced the reputation of Wagner or its owner, Yevgeny Prigozhin, a warlord, business tycoon and former convict with close ties to President Vladimir Putin – so close that he used to be known as “Putin’s chef”.

First came the news that a former Wagner fighter had escaped to Norway, where he promised to spill the beans about the group’s marauding activities. This may be the first example of a Wagner member defecting to a western country since Putin launched his invasion last February – although another Wagner mercenary wrote, before the Ukraine war, about his experiences fighting in Syria and later requested asylum in France.

In the second incident, President Aleksandar Vučić of Serbia demanded that Russian websites and social media should stop publishing Serbian-language advertisements in which the Wagner group seeks to recruit volunteer fighters. In this way, Vučić signalled that there are limits to how far Serbia will curry favour with Moscow as it pursues a foreign policy balanced between the west, Russia and China — on which, please see Dimitar Bechev’s penetrating analysis for Carnegie Europe.

Prigozhin: Rasputin 2.0?

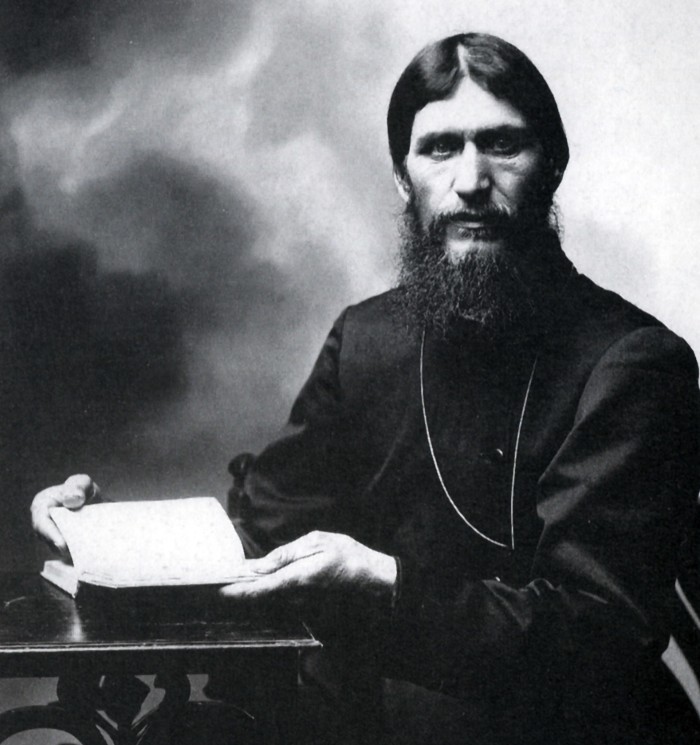

How are we to explain the rising influence of the Wagner group and Prigozhin? A couple of months ago, the scholar Andrei Kolesnikov likened Prigozhin’s role in Putin’s circle of intimate advisers to that of Grigory Rasputin, the Siberian starets, or holy man, who was a powerful and, to say the least, unconventional figure at the court of Tsar Nicholas II.

It’s an intriguing comparison, worth exploring a bit.

First, let me say that Prigozhin differs from Rasputin insofar as the latter’s influence was primarily not over Russia’s ruler but over his wife, the tsarina Alexandra — as explained in Brian Moynahan’s lively 1998 biography Rasputin: The Saint Who Sinned. The empress was susceptible to Rasputin, a self-styled faith-healer, because she had failed for many years to produce a male heir — and when she did, her infant son Alexis turned out to be haemophiliac.

Still, the comparison works in other ways. Like Rasputin, Prigozhin wields influence despite holding no formal government position. And just as Alexandra’s brain was addled by modish fin-de-siècle spiritualism, so Putin immersed himself before and during the pandemic lockdowns in the works of mystical pseudo-historians such as Lev Gumilev.

Like Rasputin, Prigozhin is assisting his master’s effort to make his most fervent hopes come true. The tsar felt he needed Rasputin’s help to stop Alexis from bleeding to death. Putin, yearning for victory in Russia’s war of neo-imperial conquest, has allowed an expanded military role for Prigozhin and his Wagner group — which, according to US estimates, now has 50,000 personnel in Ukraine, including 10,000 contractors and 40,000 recruited convicts.

Of course, Rasputin came to a sticky end. According to the tsarist police inquiry into his murder in 1916, it took a dose of cyanide, three bullets to the chest, back and head, some kicking and clubbing of the body and then immersion in the ice-cold Neva river in St Petersburg to finish him off. Prigozhin remains alive.

Maskirovka: the Russian way of war

The short-term reason for the Wagner group’s prominence is that Putin’s military campaign has stumbled. Like Chechen warlord Ramzan Kadyrov, Prigozhin has positioned himself as a searing critic of military, bureaucratic and business elites who are supposedly failing Putin with their half-hearted, incompetent approach to the war.

Wagner can do it better, is Prigozhin’s message. In a video last Saturday, he boasted that his group possessed its own aircraft, tanks, rockets and artillery, adding: “They are probably the most experienced army that exists in the world today.”

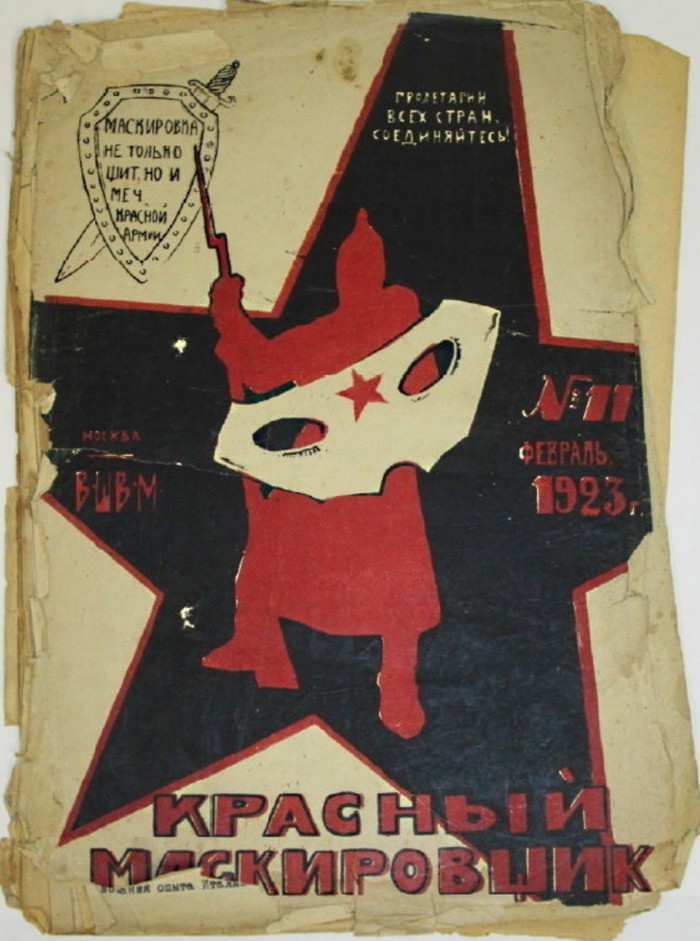

But a longer-term explanation is to be found in the rich Russian and Soviet tradition of maskirovka, which can be translated as “war by disguise or deception”. Until September, when Prigozhin acknowledged for the first time in public that he had set up the Wagner group in 2014, the organisation was a good example of maskirovka in action.

Take a look at the image below, available on the War on the Rocks website. It shows a 1923 copy of a Soviet magazine, Krasnyi Maskirovshchik (The Red Deceiver), with the slogan: “Maskirovka is not only the shield but also the sword of the Red Army”.

From its birth, the Wagner group fitted perfectly into the maskirovka tradition. For years, no one in the Kremlin admitted the group’s existence, while in practice its operations were closely connected with Russian military and intelligence units, as András Rácz wrote in 2020 for the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

The Wagner group’s main facility at Molkino in southern Russia was also the base of a special forces brigade of the GRU military intelligence agency. In Ukraine, the Wagner group has been fighting alongside the regular Russian armed forces, although this has provoked tensions as the two sides have disputed who deserves credit for recent successes.

Africa and the Wagner group

Wagner group units operate in countries such as the Central African Republic and Mali as part of what the Kremlin portrays as an effort to help legitimate governments defeat rebels and jihadists. But there are motives of Russian profit and power at work as well.

As the FT’s David Pilling reported in December, companies linked to the Wagner group have won control of a gold mine in the CAR as well as access to diamonds. In a Brookings Institution paper, Federica Saini Fasanotti explains how Russian support for the counter-terrorism operations of African governments comes at a price — concessions for natural resources, commercial contracts and access to strategic bases.

Even the ostensible goal of stabilising African governments seems elusive. In this vividly reported piece for the Associated Press, Sam Mednick quotes diplomats, analysts and human rights groups as saying that Islamist extremists have grown stronger since the Russian mercenaries arrived in Mali and indiscriminate violence against civilians is on the rise.

Prigozhin’s trolls

No account of Prigozhin’s career is complete without reference to his troll factory, which started life under the wholly misleading name of the “Internet Research Agency”. From its St Petersburg base, this operation has spewed out conspiracy theories and misinformation, chiefly for the purpose of damaging western democracies.

For this reason, the FBI put Prigozhin in 2021 on its wanted list, with a reward of up to $250,000 for information leading to his arrest.

A good book on this topic is Putin’s Trolls, by the Finnish journalist Jessikka Aro, who was relentlessly hounded by the Kremlin-backed creatures of her book’s title because of her investigations into Russian online propaganda.

Wagner veterans and politics

Does Prigozhin harbour serious political ambitions of his own? He brushed aside such rumours last year.

But earlier this month, a member of the Russian parliament’s defence committee suggested that Wagner veterans — even ex-convicts — could serve their country well by going into politics. Truly, the invasion of Ukraine is leading Russian public life into a very dark place.

Decoding the Wagner Group — a report by Candace Rondeaux for the New America/Arizona State University Future of War project

“We have conversations”: the gangster as actor and agent in Russian foreign policy — an analysis by Mark Galeotti for the Europe-Asia Studies journal

Tony’s picks of the week

-

The LockBit hacking group has a strong claim to being the world’s most prolific ransomware gang, as shown by a recent attack on the UK’s Royal Mail, the FT’s Mehul Srivastava and Oliver Telling report

-

President Kais Saied’s erosion of Tunisian democracy is isolating the north African country from foreign leaders, donors and investors, Thomas Hill and Sarah Yerkes write for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Recommended newsletters for you

Are you enjoying Europe Express? Sign up here to have it delivered straight to your inbox every workday at 7am CET and on Saturdays at noon CET. Do tell us what you think, we love to hear from you: europe.express@ft.com. Keep up with the latest European stories @FT Europe

[ad_2]

Source link